Lord North, the Georgian Prime Minster who ‘lost America’, didn’t just favour the famous tax on tea. In 1777 he proposed a levy on the luxury item of the moment: the non-essential male servant.

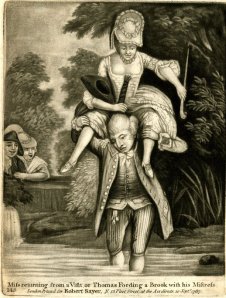

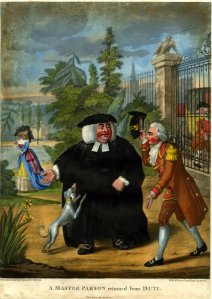

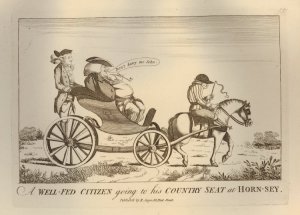

Ostensibly aimed at the wealthy, the new Male Servants’ Tax attempted to make a distinction between “productive labour and conspicuous consumption, necessary work and idle luxury”.1 Employers of the liveried, bewigged and powdered were to pay one guinea a year per male servant, including all butlers, footmen, grooms, gamekeepers and coachmen.

Employers of agricultural labourers, shop assistants, apprentices or factory workers were not liable as long as their male servants kept away from domestic duties.

In reality, the majority of taxpayers in Berkshire for the year 1780, employed just one ‘luxury’ manservant (rather than the large households envisaged by the government) and I doubt all of them wore livery.

Unlike other counties,2 the Berkshire Record Office does not have any local collectors’ books or parish returns. Instead we have to rely on the un-indexed (and not yet digitised) assessments of 1780 held in The National Archives under catalogue reference T47/8.

TNA describes T47/8 as a ‘List of persons paying duty on male servants’. When I ordered up the boxes ten years ago, I hoped to discover a hitherto untapped resource – the genealogists’ Holy Grail! I imagined a helpful list of employers’ and servants’ names, addresses, occupations and perhaps, even a few ages or lengths of service. Disappointingly, all I found was the name of the ‘Master or Mistress’ (title and surname mainly, occasionally a first name), an address (generally just the name of the parish or town unless in London, when street names were given) and the number of taxable male servants.

I made a note of all the local entries, which now form a useful, if somewhat limited, quasi-census of the servant owning class in Berkshire in 1780. For obvious reasons, it isn’t a comprehensive survey. Apart from the fact it only covers declared male domestic servants (tax evasion was rife), from a Berkshire point of view there is a huge gap in its coverage. The county’s biggest employer of liveried servants, the Royal Household at Windsor, was totally exempt from the tax and therefore not listed in the assessment!

Nevertheless, Windsor (including New and Old Windsor and the Castle) topped the chart in 1780, with a total of 59 ‘Masters & Mistresses’ employing 131 male servants!

By contrast, the man with the highest number of ‘luxury’ male servants was Lord Craven, who employed 18 at Marsh Benham (no doubt in the newly built Benham Park) and 2 at Ashbury (Ashdown House). Trailing behind him in the fashionable servant stakes was the Earl of Pomfret at Windsor with 16.

- William Poyntz of Midgham and his dog Amber

Wm Poyntz at Midgham was third with only 12, followed, in joint fourth position by Sir R’t Throckmorton at Buckland and the Earl of Fingal at Woolhampton with a paltry 10 men each. Of the ‘mistresses’, Mrs Broakhurst of Mortimer with Oakfield was taxed on 8 male servants, followed by Mrs Eggerton of Windsor on a mere 5.

Not altogether surprisingly, Reading turned out to be the perfect example of a provincial ‘every town’ in that most employers had just one man-servant: 59 taxpayers for 44 servants. Newbury and Abingdon had lower figures but the results were the same: an average of one servant per master.

Over the next 100 years, the Male Servants’ Tax was amended to the extent that it became the equivalent of purchasing a dog license. Even after the social upheavals of the Great War, it still brought in a steady income for the government. According to Winston Churchill, during the fiscal year 1923/1924 173,363 licenses were sold, producing a net revenue of £130,009.3

Always contentious, it was still being discussed in the House of Commons ten years later. During the 1930’s, questions were even being asked about its negative effect on tourism, on the basis that foreign visitors who liked to travel with their own chauffeurs(!), were not choosing to come to Britain because they did not want buy a license for them.4 However, the most pressing argument against the tax was the one first put forward by Lord North’s opponents back in the 1770’s and 80’s: imposing a duty on male servants discouraged male employment. In an era of economic depression and chronic unemployment, the tax had to go!

The Male Servants’ Tax was eventually repealed in 1937.5

Footnotes

1/ “Assessing Men and Maids: The Female Servant Tax and Meanings of Productive Labour in Late-Eighteenth-Century Britain” Susan E. Brown (2007) p.2

2/ For example Kent History & Library Centre has catalogue refs: SA/RTs/1 Servants’ Tax (including Master’s Name, Servant’s Name & Occupation) for Sandwich & Walmer 1778 & SA/RTs/2: Servants’ Tax (including Master’s Name, Servant’s Name & Occupation) for Walmer, Ramsgate & Deal 1780

Surrey History Centre has catalogue ref: 2397/5/8 Servants’ Tax Collectors’ Book (including names & occupations of servants) for Mortlake 1778

3/ Hansard HC Deb 25 March 1926 vol 193 cc1371-2

4/ Hansard HC Deb 31 July 1935 vol 304 c2685W

5/ Finance Act 1937

© Emmy Eustace

How fascinating! I had no idea this even existed… even more surprising that it was in existence so long. Perhaps an idea for the present government!

Yes, it lasted much longer than the far more controversial Female Servants’ Tax (1785-1792), which was a blanket tax on all female servants. The female version didn’t bother to differentiate between type of occupation (productive or unproductive) on the premise that female servants, unlike men or dogs, had no particular status or specialisation. Neither were maids regarded as ‘conspicuous consumption’ because unlike the dashing footman, they weren’t for public display!